Logo Data

Now that you learned how to write a procedure, it is time to talk about Logo data. You already met Logo numbers, but Logo has several other data structures. Let’s get started with some basic info.

Numbers

Logo works with numbers in many ways, from simple values to advanced mathematical calculations. Don’t worry, we’ll keep it simple here, but if you want to learn more about logarithms or trigonometry, check out the online Help files to see what else Logo can do.

Have you noticed that every instruction you want Logo to run always

starts out with the command that is followed by its inputs? You can do

arithmetic that way in Logo — type + 2 8 in the Listener and Logo will

display the result of 10 — but that’s not how people like to do

arithmetic. So Logo has bent its own rules and made the arithmetic

operators work in a special way called infix (meaning the operator goes

in between the inputs the way people like to see them). Type 2 + 8 in

the Listener and Logo will display the same result as before. Logo uses

the symbols + and - for doing addition and subtraction just like people

do. However, multiplication is done with the * symbol and division is

done with the / symbol. For example, you could move the turtle forward

30 steps with any one of these commands

FD 10 + 10 + 10

FD 50 - 20

FD 15 * 2

FD 90 / 3

You don’t need the space between the symbol and the numbers to do

calculations, but it’s easier to read. However, to make a negative

number, you must not have a space after the - symbol. Try FD -30.

You can, of course, use parentheses to group your expressions in much the same way as you would if you used a pen and paper. These are all valid Logo expressions:

(4 + 5) * 6

FD (3 * :LENGTH)

SETXY LIST 100 (:Y * 2)

You often use parentheses to feed more or fewer inputs to a Logo command than normal. Many Logo commands accept a varying number of inputs. The LIST command, for example, usually works with two inputs, but you can use parentheses to have LIST create lists of any length, like (LIST), or (LIST 1 2 3 4 5)

Words and Lists

Words and lists are two of the fundamental data types in Logo. We’ve

used words for names of colors ("ORANGE), objects ("TURTLE), and

even as a simple message ("HELLO). We’ve used a list of commands for

REPEAT, a list of numbers for

SETPC, and a list of property pairs for

PPROPS, where the list contained another

list as an element. A list that contains other lists as elements is

called a compound list, but just think of it as a list.

A list of words is a sentence — not just for you, but for Logo as well. A sentence is still a list, but it cannot have another list as an element, just words. If you don’t like computing with numbers (or math) you may find that exploring with words and lists is just the thing for you; areas like poetry, silly sentences, foreign language translation, and linguistics are some examples.

Words and lists are everywhere in Logo. There are many commands and operations that work with both, depending on the input you give. Here are examples of some of the most common operations. Fortunately, with many Logo instructions, you can tell what they’re for just by their name. Check out the Help files for more information. Try using your own name.

| Examples with words | Examples with lists |

|---|---|

| FIRST “COMPUTER Result: C LAST “COMPUTER Result: R BUTFIRST “COMPUTER Result: OMPUTER BUTLAST “COMPUTER Result: COMPUTE MEMBER? “P “COMPUTER Result: TRUE BUTMEMBER “P “COMPUTER Result: COMUTER EMPTY? “COMPUTER Result: FALSE WORD “COM “PUTER Result: COMPUTER WORD? “COMPUTER Result: TRUE |

FIRST [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: TERRAPIN LAST [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: LOGO BF [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: [LOGO] BL [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: [TERRAPIN] MEMBER? “LOGO [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: TRUE BM “LOGO [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: [TERRAPIN] EMPTY? [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: FALSE LIST “TERRAPIN “LOGO Result: [TERRAPIN LOGO] LIST? [TERRAPIN LOGO] Result: TRUE |

Operations (Your OUTPUT matters too!)

An operation is a command that outputs a value that can be used as input

to another command. Operations are also called reporters because they

report (or output) a value. The procedures we’ve written so far do their

job and then just stop: we didn’t need an output from them. Wouldn’t it

be silly if SQUARE output the message “I’m done now” every time it

drew a square? You can ignore unwanted outputs by using the IGNORE

command; it takes any input and throws it away. To make your own

operation, use the OUTPUT command in your

procedure. It takes one input: the value you want reported (or output).

When the OUTPUT command is run, your

procedure stops and the value of the input to

OUTPUT is output for input to something else.

So, make sure your procedure has done all its work before the

OUTPUT command is run. Ever heard “garbage

in, garbage out?” Don’t do that.

There is not a built-in operation called SECOND but we can make one.

SECOND will report the second element of a word or a list in the same

way that FIRST reports the first element. Define SECOND and then try

some examples using words and some using lists.

SECOND.lgo

``` file

TO SECOND :INPUT

OUTPUT FIRST BUTFIRST :INPUT

END

```

How about making THIRD your second operation since SECOND was your

first? You could use your first operation inside your second because the

third element is the SECOND of a

BUTFIRST! 4ths anyone? I’ll take the

fifth.

Decisions

Big decisions are made with one little word: IF. So far, our procedures have just run commands in the order in which we wrote them. It’s like we were saying “Do what I say!” to our procedure and it did it, no questions asked. Programs that make decisions have a sense of intelligence about them. They seem to be smart enough to do the right thing at the right time for the right reason (usually!). It’s like the program is saying “I can make my own decisions!” One way that decisions are made in Logo is with the IF instruction, which is usually put on a line by itself. A simple form of IF is: IF predicate THEN instruction

A predicate is an expression that evaluates to either the word TRUE or

the word FALSE. The instruction after THEN is only run when the

predicate evaluates to TRUE. It should not be a surprise that most of

the predicates in Logo have a question mark at the end of their name

since a question can determine if something is TRUE or FALSE. Some

of the most commonly used comparison operators are another exception to

the “command first” rule and allow you to put them in between the two

inputs you want compared. For example, the equal sign ( = ) compares two

inputs and reports TRUE if they are equal and FALSE if they are not

equal. Both of these examples do the same thing.

IF :SIZE = 10 THEN STOP

IF = :SIZE 10 THEN STOP

Most people like the first example better, another infix choice.

Recursion

With one small decision (and a minor calculation), a simple procedure can become a masterpiece of design. Without that little decision, things can get out of control and cause an ‘infinite loop’ — a technical term for a program that will not stop on its own. Of course, sometimes the infinite loop is actually a plan, usually for a demonstration of some kind.

A procedure that runs itself is said to be recursive - the running of the procedure recurs (or repeats) over and over again. Isn’t this just an infinite loop? It could be, but we are going to control it. How? First, we will have a formal input that we can modify each time the procedure runs itself - something must change each time. And, we must define a way for stopping the procedure from running itself - a condition must be met. All of this may sound very complicated (and it is) but with an example procedure, most of it will be clear as … glass.

Here is a simple procedure that draws a line of length SIZE and then

turns right 90 degrees.

TO LINE :SIZE

FD :SIZE RT 90

END

It’s not very impressive, but suppose we change it so that after a line

is drawn of length SIZE, it runs LINE again but with a slightly

bigger SIZE? Define LINE and run it. Yes, it is an infinite loop,

but this is just a demo. Press the Stop button to stop it.

TO LINE :SIZE

FD :SIZE RT 90

LINE :SIZE + 5

END

So, now we have a formal input and we modify it each time, but we still

need a way to stop LINE from running itself repeatedly. Since SIZE is growing

bigger and bigger, how about checking it each time and then, when it

gets greater than 100, we just stop?

What we need is an IF instruction. If SIZE is

greater than 100 then stop. An instruction that makes the decision to

stop a recursive procedure is called a stop rule. Where does it go?

Certainly, it has to be before LINE is run again, but should it be

before a line is even drawn by FORWARD?

You can try it both ways and see what the difference is. Try different

inputs.

TO LINE :SIZE

FD :SIZE RT 90

IF :SIZE > 100 THEN STOP

LINE :SIZE + 5

END

Add a second input called ANGLE so that you can make the turn anything

you want.

Add a third input called INCREMENT and use it to change SIZE instead

of 5.

There is a lot more to learn about recursion to fully understand it. This is just the beginning. Imagine!

Variables (MAKE some THING)

The only variables we used so far were the formal inputs to procedures. You can create your own variables in the Logo workspace. To see them, type PONS (short for PRINTOUT NAMES). The workspace is also referred to as the “global environment” because variables created there are accessible by procedures as well as you. The formal inputs to procedures only exist while the procedure is running. These variables are created in the “local environment” of the procedure. You can’t get at them while the procedure is running and they go away when the procedure ends. When writing programs, it’s important to know where variables are created.

Every variable has a name. A name is a word. To use a word as itself,

put a double quotation mark in front of it so that Logo won’t think it’s

a command and try to run it. Every variable has a value associated with

it, even if it’s the empty word or the empty list, which look like

nothing. To create a variable in the workspace, give

MAKE the name of the variable and the

value you want to assign to it. To use the value of a variable, give the

name of the variable to THING. The

following examples create one variable named STEPS with a value of 20

and another variable named INCREMENT with a value of 10.

MAKE "STEPS 20

MAKE "INCREMENT 10

THING is an operation that reports (or outputs) the value associated with the variable whose name you give it as input.

THING can be used wherever you need a value.

FD THING "STEPS

would move the turtle 20 turtle steps. The output of

THING is 20, which is used as the input to

FORWARD. You can change the value of a

variable by using another MAKE command

with a new value. The value can be just a number, a calculation, the

output of an operation, or any Logo data value. It’s usually a good idea

to assign the same type of data to the same variable. For example, since

I used STEPS for numbers, I shouldn’t put “LIVELY in it later on.

That just invites trouble and could be very frustrating. Most other

programming languages force you to use the same type of data again but

it’s not a restriction in Logo. Restriction or not, it’s a good idea.

In the following example, you can see that the use of THING can get pretty messy and awkward. Just imagine trying to add four or five values together!

MAKE "STEPS THING "STEPS + THING "INCREMENT

Don’t worry. Help is on the way! Are you familiar with emoticons

(emotion icons) — things like :) for happy and :( for sad? If you treat

this page like a turtle and ‘run’ a RIGHT 90, you’ll see a smile and a

frown. The colon character looks like a pair of eyes. That’s exactly

what the Logo shortcut is, a colon in front of a variable name acts

like a pair of eyes that lets you ‘see’ what the value of the variable

is. Of course, by ‘see’ I mean it outputs the value.

A value stored into a variable is also called a “Name” in Logo.

Dots: A THING, I See!

The colon is called ‘dots’ in Logo. Dots takes the place of both THING and the double quotation mark in front of the variable name. It saves a ton of typing! The example from above can be written much more simply now.

MAKE "STEPS :STEPS + :INCREMENT

When you read instruction lines or say them out loud, it’s a good idea to say the word ‘dots’ for the colon and ‘quote’ for the double quotation mark. So, this line would be said as “Make quote-STEPS dots-STEPS plus dots-INCREMENT.” Without even seeing the line, another Logo person would know that quote-STEPS meant the variable name and that dots-STEPS and dots-INCREMENT meant the values. You’ll find this to be a big help while learning and a good habit to stick with.

Think Locally

Usually, variables are stored in your workspace; every procedure that you run, or every command that you enter finds this variable. Here, we are talking about global variables.

Within a procedure, things can be quite different. A procedure input, for example, is a variable that is only known to the executing procedure (and all procedures that this procedure calls). As soon as the procedure ends, the variable is gone.

This is actually a great thing! You can keep data that is important only to your procedure within that procedure. Actually, one of the hardest bugs to find in a program is a procedure that accidentally overwrites a global variable. Look at this code, for example:

TO SAY.IT :N FOR “I 1 :N [PRINT [I WILL NOT BITE MY NAILS]] END SAY.IT defined TO COUNT.SAYS SAY.IT 5 MAKE “I :I + 1 END COUNT.SAYS defined MAKE “I 0 COUNT.SAYS

SAY.IT prints a sentence N times, and uses the variable :I to keep

track of the count. COUNT.SAYS tracks the usage of SAY.IT and counts

how often it is called in :I. Now, what do you think that :I contains

after the first COUNT.SAYS command? 1? Sorry, you are wrong! The

value of :I is 7! Certainly not the value that you expected.

Do you see why?

Because SAY.IT uses the global variable :I to count! And that

confuses COUNT.SAYS totally.

SAY.IT should really have used a variable that would have lived only

inside SAY.IT itself.

Luckily, Logo offers the LOCAL command just

for the purpose to declare a variable to be local to a procedure. So,

here is the corrected version of SAY.IT:

TO SAY.IT :N LOCAL “I FOR “I 1 :N [PRINT [I WILL NOT BITE MY NAILS]] END

This is a very important feature. Avoid the hunting of unexplained changes of global variables by using LOCAL liberally within your procedure!

Logo also offers the LMAKE command, which is a combination of the

LOCAL and MAKE

commands.

Properties

Many things in Logo have their own property list — turtles, controls, and things we haven’t seen yet. A property list is a special kind of list containing property pairs; a property pair is a property name and a property value that is associated with that property name. That’s a rather long-winded definition, but it’s important.

Property List Commands

There are many Logo commands that indirectly affect many of the properties of objects. However, some properties can only be modified with either the property list editor or the property list commands. The property editor is convenient while you’re exploring but, in a procedure, you may have to use the property list commands.

Get a property value

GPROP is an operation that reports (or

outputs) a property value. It needs two inputs: the name of the object

and the property name whose value you want. For example, GPROP 0

“PENWIDTH. If you use a property name that is not in the property

list, GPROP outputs the empty list (a

pair of brackets with nothing between them, []).

Put a property pair

PPROP is a command that either adds a

new property pair or modifies an existing property value. It needs three

inputs: the name of the object, the property name and the value you

want to assign. For example, PPROP 0 "PLANET "EARTH.

Put many property pairs

PPROPS is actually a shortcut form of

typing a lot of PPROP commands. It needs

two inputs: the name of the object and a list of property pairs. For

example, PPROPS 0 [PLANET EARTH RUN [FD 100 RT 90]] is the same as the

two commands PPROP 0 "PLANET "EARTH and PPROP 0 "RUN [FD 100 RT 90].

You can also view property lists as a sort of mini-database. Let’s look at a few personnel records:

PPROPS “JACK [AGE 41 GENDER MALE EYES BLUE] PPROPS “JILL [AGE 35 GENDER FEMALE EYES BLUE] PPROPS “JOE [AGE 35 GENDER MALE EYES GREEN] MAKE “PERSONNEL [JACK JILL JOE] ; create a procedure to list all properties with a certain value TO SELECT :PROPERTY :VALUE LMAKE “RESULT [] ; create a local variable RESULT ; iterate through all personnel FOREACH :PERSONNEL [IF (GPROP “? :PROPERTY) = :VALUE THEN MAKE “RESULT LPUT “? :RESULT] OUTPUT :RESULT END SELECT defined SELECT “AGE 35 Result: [JILL JOE] SELECT “EYES “GREEN Result: [JOE]

This example of a database search is very simple. Try to expand SELECT

so you can supply the comparison operator instead of comparing for

equality!

The Property List Editor

Logo comes with a built-in editor for properties. For most visible objects, like panels, turtles, buttons, and the like, simply right-click the object to open its property editor.

The property editor displays the most important properties of an object. If you would like to edit all of its properties, click the small list icon (View All) in the property editor’s header bar.

Once you change a property, the change takes effect immediately. Try, for example, to right-click turtle #0 and to change its pen color. Also, if you enter a PPROP command into the Listener, the property editor displays the change immediately.

If a property has been changed, a small red X appears next to the value. If you click this X, the property resets to its initial value.

A word about colors. When you click a color, the browser’s color picker appears. It does not let you select the opacity of the color, unfortunately. Therefore, transparent (invisible) colors appears as black in the property editor, and if you change the property to black, the color actually appears as black, because its alpha (transparancy) value is gone.

For objects and property lists that are not visible, use the

EDPLIST command as in EDPLIST “PREFS

to invoke the property list editor.

Turtle Properties

All Logo widgets (turtles, bitmaps, and controls) have a huge number of

properties. Actually, many Logo commands are only shortcuts for

accessing properties of the widgets that are part of the

TELL list. This may lead too far for now,

but just try the command PLIST 0 to see turtle 0’s properties.

Now, set the heading of turtle 0 to 90 degrees. No, do not use SETHEADING; use turtle 0’s property list!

PPROP 0 "HEADING 90

The same applies to the position, the pen color, and much more. Feel free to experiment with turtle 0’s properties. You can find a description of all available properties on this page.

Animals, Birds, Fish, and Other Pictures

Finally! We’re ready to explore and play

around with some very colorful objects called bitmaps. Bitmaps are a lot

like turtles except they don’t have a pen. Logo includes many different

bitmaps.

Finally! We’re ready to explore and play

around with some very colorful objects called bitmaps. Bitmaps are a lot

like turtles except they don’t have a pen. Logo includes many different

bitmaps.

Open the Toolbox and then select the Sealife panel and drag a whale out to the Graphics panel.

Once it drops, Logo tells you the name of the bitmap, like for example WHALE1.PNG.

Now, you can maniuplate the heading, the size, and much more in two ways. You

either use PPROP or

PPROPS to change the whale’s

properties, or you use the command TELL "WHALE1.PNG to talk to the whale

instead of the turtle. Then, you can work with the whale as if it were a

turtle.

Make it splash!

Most widgets have a RUN property. You can set that property to a list

of commands the Logo should run whenever you click the widget. For now,

let’s make the whale splash every time you click it with this command:

PPROP "WHALE1.PNG "RUN [PLAY "SPLASH]

Controls (Click on This!)

The Toolbox Controls panel has a variety of controls that make your programs easier for others to use. You have probably seen all of these controls somewhere before, either in Logo or in other applications that you run on your computer. They are standard visual programming tools for developing a Graphical User Interface (GUI). Now, you can put them in your own Logo programs!

All of the controls can be placed in the

Graphics window by dragging them with the mouse. Each control is given a

name, like

All of the controls can be placed in the

Graphics window by dragging them with the mouse. Each control is given a

name, like BUTTON.1 for the first button and BUTTON.2 for the second

button. You can change the name in the properties dialog or with the

PPROP command. You can also create

controls with the DECLARE and

NEW commands. To move a control, hold down

the Shift key while dragging it to a new location. Controls can be given

commands just like bitmaps - using ASK or

TELL. To get rid of a control, type

ERASE and give it the name of the control.

When you type CLEARSCREEN to clear

the screen, all of the controls are erased.

There are eight different controls. The Editbox, Listbox, and Popup listbox

are used to get text input; the Checkbox and Radiobutton are used to

indicate a choice (like true/false or yes/no); the Textbox is for

displaying text; the Button is for starting some action. Finally, the

Grid control lets you arrange text or other controls, turtles, or

bitmaps in a grid. Many of these controls have special properties that

can be called with the help of the CPROP

command. If you want to be informed when the user clicks a button or

selects a listbox item, you should also set its RUN property to a list

of commands (or a procedure call) that processes the user’s choice.

You can create bitmaps, turtles or controls (we call them “widgets”) from within a Logo program; use the NEW or DECLARE commands for this purpose. Also, you cannot redeclare a widget. If you want to reuse the widget’s name, erase the widget with the ERASE command first.

Just as a teaser, try out this small program; it creates a list box, populates it with a few items, and prints the selection when you click one of the items:

DECLARE “LISTBOX “JOE (CPROP “JOE “APPEND [ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE]) PPROP “JOE “RUN [PRINT GPROP “JOE “TEXT]

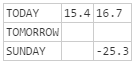

Grids

A Logo grid is a special control that lets you

arrange text or widgets in a grid. This makes a grid a very powerful

feature, because it is not necessary to re-align controls because of

changes to the display size when you store them in a grid.

A Logo grid is a special control that lets you

arrange text or widgets in a grid. This makes a grid a very powerful

feature, because it is not necessary to re-align controls because of

changes to the display size when you store them in a grid.

Grids also make fabulous-looking tables very easy. Create a grid, set its dimensions, and start to fill in your data!

Further Programming

All of the exploring and playing around we’ve done is a part of learning to write programs in Logo. After all, to do any job well, you have to learn what tools are available and how to use them. Logo is much more than turtle graphics, pictures and sounds. It’s a powerful language for problem solving, calculating with numbers, manipulating words and lists, and learning concepts of computer science and programming.

A program can be as simple as one procedure like MY.GRID. It has a

definite purpose or goal - in this case, to make a small graph for

designing turtle shapes. It uses the tools of the language and puts them

together in a sequence of instructions to get the job done. A person

running MY.GRID doesn’t need to know how a graph is made, only

that MY.GRID will make a graph every time it’s run. But you, as the

programmer, need to know all the gritty details that make it work

correctly. It’s a challenge at times, but also interesting, intriguing,

fascinating and sometimes frustrating, but always rewarding when your

program works properly.

A big program shouldn’t be just one huge procedure trying to do it all. You may need a lot of little procedures to do a big project, with each procedure doing just a little bit of a big job. You’ll find that many of your small procedures will be useful in other projects. Save them in their own file so you can include them in other projects without defining them again. You can build your own library of special procedures, use them when you need them, and share them with other Logo programmers. There is so much more to Logo programming - I hope you explore!